By Hannah Heller, nikhil trivedi and Joanne Jones-Rizzi

***

Introduction

Before we dive in, we’ll begin with a brief example of white supremacy culture in a situation encountered by friend and colleague Joanne Jones-Rizzi, Vice President of Science, Equity, and Education at the Science Museum of Minnesota:

WHEN IS IT NOT WHITENESS? White supremacy culture is the norm. It represents the prevailing way of thinking and it is normalized in our everyday interactions and museum culture. White supremacy culture is dominant in thinking, speaking, dressing, behaving, meeting styles, language, and communication. For those who challenge this norm, it takes courage, confidence, frustration, or fury. I tend to overthink it, weighing reactions, impact to others, to myself. What will it mean? Who will be hurt? Who will be angry? Who won’t understand? How much will it cost me? My overwrought hand-wringing is symptomatic of the insidiousness of white supremacy culture and how it works its way into our psyche and erodes our self-esteem, self-worth, and self-confidence. Survival is real. We all have our own levels of tolerance and abilities to show up each day to work within a culture that negates Brown, Black, and Indigenous people and renders us invisible.

A recent experience illustrates my point. I learned of a colleague who is editing a volume on issues related to Museums and Equity. The editor is planning to pair researchers and museum practitioners. I learned from another colleague, who has been invited to write for the volume, that she is the only POC on the list.

I stewed about it for a while and voiced my concern to another colleague, unsure how or what could be done. I tried to understand my reaction and also how I might shift the planning to include the perspectives of more Brown, Black, and Indigenous voices.

Rather than fret and complain to my colleagues, I decided to write to the editor, who is white. The editor and I met years ago, during a period when I had a two-month long fellowship in residence. I remembered them, and I assumed they would remember me. I began by saying that I had learned about the planned volume, that I was excited to know about it, and looked forward to reading it when it came out. I went on to explain that I was writing with unsolicited advice about the intended volume on issues related to museums and equity. I asked the editor to consider inviting more researchers and practitioners of color and Indigenous people. I added that the proposition raised fundamental questions about equity and inclusion practices in museums from researcher and practitioner perspectives. I suggested that the editor think about: who does this work, how is the work framed, who benefits from this work, and who are the people who are sacrificed in this work. I asked the editor to consider the position they hold, the privilege and power they have, and to think about how their lived experience informs their perspective on equity.

Writing to the editor was the right thing for me to do at this time in my career and in my life. Challenging White supremacy culture in this instance felt critically important to me. The editor did respond with an email, thanking me, explaining the rationale for the volume and noting that the “list” was still evolving. The response had a respectful tone, and on one level was appreciative while also explicating the “lack of a deep bench” that they perceived as a limiting constraint to inclusion. I’d like to believe that I shifted how this individual thought about the planned volume and its intent, impact, and relevance.

White Supremacy culture has a way of creating erasure or making us and our ideas invisible, even when we are in plain sight. When the editor ended the response by thanking me, and hoping that we would meet one day, their act of erasure was in plain sight to me. Even with my generous albeit unsolicited email/ correction/suggestion I was invisible. It was so subtle it might have gone unnoticed, but I noticed. There it was, White supremacy culture, inside of a White supremacy scenario, showing up again.

Joanne’s story makes clear that one of the many challenges of addressing racism and White supremacy in our workplaces is the fact that white people have constructed whiteness to be rendered both normalized and invisible in our daily lives—a challenge that is also true for oppression more broadly. In her story, the editor’s choices reflect a bias—be it conscious or unconscious—that white people could best speak on equity in the field and could do the best research on the topic. Because white people’s internalized white supremacy endows themselves with the power and ability to speak on any topic.

We typically talk about the construction of race in a passive sense (“race is socially constructed”), without acknowledging who is responsible for these constructions. The white dominant group has always defined and fabricated characteristics of each racial group, including their own. Toni Morrison in her book Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination articulated the invisibility of whiteness in this way:

“It is as if I had been looking at a fishbowl — the glide and flick of the golden scales, the green tip, the bolt of white careening back from the gills; the castles at the bottom, surrounded by pebbles and tiny, intricate fronds of green; the barely disturbed water, the flecks of waste and food, the tranquil bubbles traveling to the surface — and suddenly I saw the bowl, the structure that transparently (and invisibly) permits the ordered life it contains to exist in the larger world” (p. 17).

bell hooks describes it as “a state of unconsciousness,” where whiteness (and maleness, straightness, etc) is the presumed identity of people in power, and anyone who represents the “other” is seen as anomalous—for example, it is rare to name an artist as being white, but we often go out of our way to name the racial identity of an artist of color, suggesting that a POC artist’s race is relevant, where a white artist’s race is not. As another example in our field, we label museums representing cultures of POC as “culturally specific,” while museums representing the dominant white culture absolutely also have their own (unnamed) cultures, values, and biases rooted in White supremacy. Only by making these visible, naming them, and identifying them in our own institutions can we begin to subvert them.

Our starting point is literature predominantly written by women of color in our field—particularly Black women—that describes the experience of White supremacy in museums, dismantles the notion of neutrality in museums, takes on structural racism as it relates to our professional orgs, speaks to the important conversations on racial equity happening on social media, the need for a complete understanding of Critical Race Theory in this work, guidelines for allies working towards these goals, the importance of grounding practical knowledge in Critical Race Theory and anti-racist theory, and the collective work of the MASS Action advisor team and the resources they provide.

In this post we hope to contribute to this ongoing conversation on racial equity and White supremacy in museums by describing specifically what obstacles white culture places in the way of doing our best work and offer some constructive ways to subvert it. Specifically, we draw from educators and activists Kenneth Jones and Tema Okun (a Black man and white woman respectively), whose work focuses on naming those cultural attributes of whiteness and White supremacy in organizations. While they outline several (we recommend a full read), we pulled out a couple that resonate strongly in our museum work as educators and community builders, and that haven’t been fully addressed in museum contexts (whereas things like white comfort and/or fragility, huge aspects of white culture, tend to get a lot more attention).

Jones and Okun remind us that many of the following are not necessarily “bad” traits in and of themselves—putting things in writing and honoring deadlines are important and often helpful. The issue becomes when we privilege these white ways of thinking and knowing and doing business above all others.

Worship of the Written Word

Jones and Okun describe this one as simply, “if it’s not in a memo, it doesn’t exist.”

As institutions that come out of academic disciplines, we have a strong relationship with written histories. We rely on documented narratives of the past to produce our exhibitions and legitimize our collections, and we gauge our own authority by our production of researched texts. This pattern reflects a culture of White supremacy, and it severely limits our ability to think well about communities whose histories have been systematically erased over time.

In the United States, for example, documentation of Indigenous perspectives of Native genocide is much more rare than the perspectives of white settlers. Stories detailing the lives of enslaved people were often documented by and through the lens of their white owners. Documents that survived times of war were often controlled by those who ended up on the winning side of the conflict. Relying on written histories as heavily as we do has led museums to rehash history from a white perspective over and over again. Take Joanne’s story for example; in considering pairing an institution with an expert to discuss a social justice issue affecting their audiences, why is a white researcher considered a better resource than someone who acutely experiences racial inequity?

On a more practical note, our overreliance on the written word impacts our day-to-day as well. For example, museum educators are often required to submit lesson plans in writing (labor that is typically unpaid) in order to demonstrate our planning. But writing may not be the most beneficial approach to planning lessons for every educator. Managers might consider alternative ways of demonstrating planning that doesn’t include putting in words what we can only plan for in the moment, or that might be better documented visually, graphically, orally, etc. Maybe it’s scheduling a brief (paid time) phone call, or sharing lesson plans with the whole education team.

As an antidote, we first need to name and unpack our relationships with written histories and aspects of our work. Jones and Okun offer that we “accept that there are many ways to get to the same goal.” What is at the root of our professional reliance on the written word? What feelings come up when we consider not relying on them? Can we conceive of alternative approaches? If we can’t imagine it, why not? Jones and Okun offer another useful antidote we can move towards next: “be clear that you have some learning to do about the communities’ ways of doing.” We can give more weight to histories and work documented via more popular, democratic means: oral histories, stories passed down to descendants, narratives told through artworks, emphasize collaborative processes over predetermination, etc. It can become a practice where we believe our collaborators, and see where that takes us. Again, it’s not to say don’t write anything down ever (especially in the growing push to write DEAI plans as an example), but consider balance and intentionality: how am I documenting this information and why?

Paternalism

We see paternalism play out in a number of ways in our organizations, including a lack of transparency around decision-making or a wide gap in understanding between those making decisions and those affected by them.

Paternalistic organizations are often heavily hierarchical and siloed. This can result in a large distance between those that hold the most positional power and those who hold the least. And the experience of that distance can be magnified if you’re from a marginalized community—if you’re a woman, a person of color, working class or poor, queer, trans, a person with disabilities and so forth. If you’re simultaneously from multiple marginalized communities, that magnification is further compounded.

In a recent Twitter conversation, women talked about the constant hand-slapping they experienced while taking risks, to a point that slowly sidelined their authority. This is another way we see paternalism in our organizations: different allowances of authority in practice than what’s decided by the organization.

Jones and Okun’s antidotes to paternalism mainly center around transparency. Slow down, and focus on communication and processes over outcomes. Make sure everyone affected by decisions has a way to engage in the decision-making process, and give a lot of time for that engagement. Our organizations may have to slow down to enact these solutions, so remember that our sense of urgency is another characteristic of White supremacy culture, and take your time.

Perfectionism/Risk Aversion

As museums, we define our own value by our authority—the (false) perception that we present and share full and absolute information from an objective, unbiased perspective. Because of this, we have immense fears of making mistakes. We’ve trapped ourselves into a conundrum where we can’t say or do *anything* unless we’re absolutely certain that it’s perfect.

Jones and Okun sum up this characteristic with a sentiment many of us have seen: “making a mistake is confused with being a mistake.” We embody this within entire organizations. We see the risk of making a mistake as being so great that our perfectly constructed public perceptions will come tumbling down and we feel our organizations will be seen as a mistake. This may explain why the editor in Joanne’s story was so reluctant to take the well considered suggestions to heart; to acknowledge a mistake, apologize, and make the necessary changes is much harder than ignoring said advice and moving on.

One way this manifests is in the way we interpret our collections and artists for visitors. If curators aren’t absolutely certain of an object’s provenance, or year it was made, that information often becomes obfuscated to the point of unintelligibility, or left out entirely (the impact of this exclusion on interpreting queerness is well documented by Margaret Middleton’s work). How refreshing would it be if we felt open and honest when we aren’t able to know things absolutely? We might see interpretive text like, “we believe this comes from X place in Y year, but we can’t know for certain for ABC reasons.” We might even follow that with a question for our audiences: “What do you think?” We could demonstrate to visitors the complicatedness of researching objects, and let them in on our process.

We likely also see this at play in our programmatic efforts; museums move SLOWLY, programming requires an extremely coordinated effort, and particularly in larger institutions this process can involve months of emails and meetings and back and forth. We do this to ensure we’re minimizing risk and doing our best work. But when a programmatic need arises that is time sensitive and/or reacting to a timely political moment, this way of doing business may not serve our (or our audiences’) best interests. Sometimes a program or institutional response demands a more nimble approach. This way of working is often conflated with risk, which demands further introspection—what really do we mean by “riskier”?

But making this shift can be hugely beneficial; not only can we address our communities’ needs and concerns in a timely fashion that respects their priorities, but it opens up a whole new approach to programming! Again, we don’t mean to suggest that all programs should happen reactively within a short timeframe, but perhaps we might look at in-the-moment programming as an opportunity to develop and expand our programmatic skill sets.

Jones and Okun remind us that avoiding conflict is yet another aspect of White supremacy culture and mistakes are opportunities for learning. Let’s lean into discomfort and try to introduce programs that center the priorities of the marginalized communities we serve, be transparent with our audiences about our limitations, and learn from teachable moments. Authentically responding to our communities in this way will slowly build trust over time. It can work us towards some of Jones and Okun’s suggested antidotes for separating the person from the mistake: “develop a learning organization” where we’re always learning and growing, and “create an environment where people can recognize that mistakes sometimes lead to positive results.”

Sense of Urgency

White people LOVE deadlines. They set meetings to set deadlines. They have deadlines to set deadlines! While doing things in a timely fashion isn’t a bad way to work necessarily, deadlines can often present a detriment to our work, rather than help. Jones and Okun frame this issue as prioritizing timeliness and “funder-driven deliverables” over taking the “time to be inclusive, encourage democratic and/or thoughtful decision-making, to think long-term, to consider consequences.” They explain that this often results in “sacrificing potential allies for quick or highly visible results”. Here they provide the example that many of us in museums are familiar with: “sacrificing interests of communities of color in order to win victories for white people (seen as default or norm community)” and forcing through rushed funding applications that “promise too much work for too little money and by funders who expect too much for too little.” In other words, in prioritizing a sense of urgency, we may lose the “why” of our work.

We see this largely in terms of community work. It takes time to develop authentic, trusting relationships, and in the meantime, we may feel rushed to push through funding applications without the amount of relationship building required to do this work well.

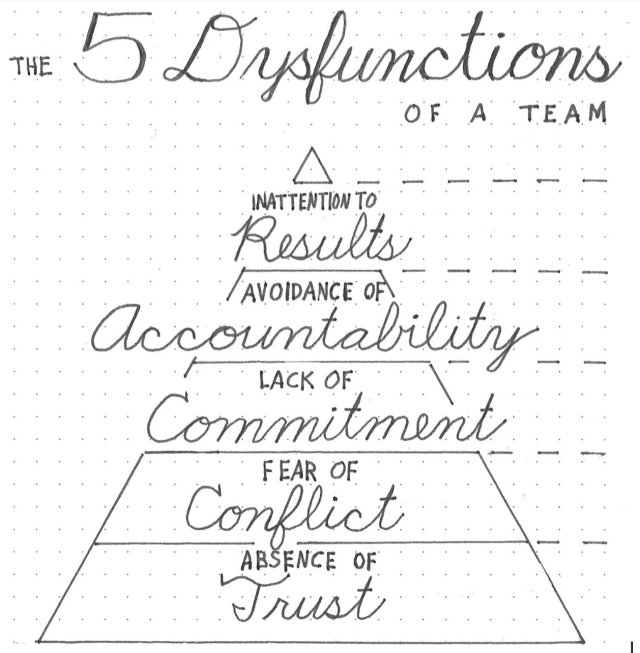

Five Dysfunction of a Team Pyramid.

In his book Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick Lencioni describes the factors of an effective team as being grounded in trust. Trust leads to healthy, open conflict, commitment to decisions, accountability to seeing them through, and producing results. Although oriented to a business audience, this pyramid illustrates how fundamental trust is, and all that’s required between trust and producing effective outcomes. Moving at the speed of trust is the most important gauge of time we can follow.

It’s not to say don’t plan for anything ever, but as Jones and Okun recommend, we need to think realistically about, “what it means to set goals of inclusivity and diversity, particularly in terms of time,” and communicate these expectations to museum leadership. If something is due on a particular date, perhaps we can rethink how we work between now and then to make sure we’re honoring our primary goals. Jones and Okun make the point that “rushing decisions takes more time in the long run,” because “inevitably people who didn’t get a chance to voice their thoughts and feelings will at best resent and at worst undermine the decision because they were left unheard.” Rushing relationship building only undermines the relationship in the long run. Let’s figure out ways we (as individuals and our institutions) can slow down and be in the moment. This intentionality will better equip us to serve us and our audiences.

Transactional Relationships/Goals

If we champion the idea that museums are for our audiences, and that our primary work is in their service, then many of our institutions need to reconsider the nature of our institutional (as well as personal) relationships with our various audiences. Too often “community” work is conducted from a deficit model, where the institution is seen as the entity with information, value, and cultural capital to share with our underserved, “at-risk,” lacking-in-cultural-capital audiences, oftentimes with the unstated goal of using them in our reporting over-simplified, tokenized successes to funders. Our observation is that museums rarely develop community programs with the goal of actually learning from these valuable audiences. Our audiences serve as a major resource for us to learn how to do our jobs better. If this isn’t our orientation to community work, we will consistently struggle to meet our missions.

We need to reorient ourselves, and consider more deeply what we can learn from our audiences through working together. Jones and Okun recommend building relationships—both internally and externally—that “are based on trust, understanding and shared commitments.” She draws our attention to the “simplest ways”—getting coffee, greeting and acknowledging each other (novel!), especially, she says “when there’s ‘no time’ to do so.” Can we develop ways to “share in each other’s cultural bounty”? Can we deliver on a grant’s quantitative requirements, as well as develop our qualitative goals for engagement?

Conclusion

A typical question we’ve heard following these ideas is, “okay, I get that too much urgency, or risk aversion, or treating our community relationship as transactional are negative qualities in our work. But how do you know it’s whiteness, and not just plain old organizational culture?” Our response is simple: if we know our society and culture is dominated by White supremacy, it follows that our workplace cultures are as well. If we know that “universal” and “generic” ideas and behaviors default to white, the analysis of our cultures must speak to this as well (see the importance of understanding the intersection of this work with important theoretical concepts like Critical Race Theory mentioned above—to get started explore LaTanya Autry’s incredible compilation of readings here). As illustrated by Joanne’s example at the beginning of this article, and similarly voiced by scholar Ibram X Kendi, any given policy or practice is either creating racial equity or creating racial inequity. There is no neutral ground. In decentering whiteness in our professional lives, white people need to start seeing their ways of doing and knowing as just one option among several. Jones and Okun provide a valuable framework from which to do so.

Please continue the conversation by commenting with examples of White supremacy culture you’ve seen, whether driven by the attributes we described above, or by one of the many other aspects of White supremacy culture Jones and Okun mention in their work. Feel free to suggest your own field specific antidotes as well!

***

nikhil trivedi is the Director of Engineering at a museum in Chicago and a social justice activist. As a facilitator and educator, his activism work focuses on institutional healing and accountability from historic traumas like colonialism, slavery, genocide, and war. He’s a long-time volunteer with Resilience, Chicago’s largest rape crisis center, is a regular contributor at The Incluseum, and his writing has been featured in Model View Culture, Fwd: Museums and the Journal of Museum Education. At his museum, he enacts his values of transparency and openness through sharing a large amount of data through their public API, having his team work in public code repositories, and through his leadership in the museum’s Equity Working Groups. You will also find him playing guitar and sitar, hiking, making herbal medicines, and drinking warm glasses of chai on cold winter nights. Connect with him on Twitter @nikhiltri, and learn more about his work at nikhiltrivedi.com

Hannah Heller is an NYC based freelance museum educator, and has taught and worked on research and evaluation projects in several cultural institutions including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Inc., Whitney Museum of American Art, El Museo del Barrio, the American Folk Art Museum, and the Museum of Arts and Design. She is currently a doctoral candidate in the Art & Art Education program at Teachers College, and holds a MA in Museum Education from Tufts University. Her current research focuses on anti-racist pedagogies and ways to mitigate the effects of whiteness in gallery teaching practices. Follow her on Twitter @museum_matters

Joanne Jones-Rizzi serves as the Vice President of Science, Equity, and Education at the Science Museum of Minnesota, where she leads the Science Museum’s science and education initiatives, ensuring that they achieve maximum impact and are equitably accessible for all audiences. Jones-Rizzi has a decades-long career working on systemic, ecological change within museums, specializing in expanding meaningful access through exhibitions relevant to audiences who do not yet think of museums as their cultural institutions. She advises museums nationally and internationally on culture, identity, anti-racism, exhibition development, and community engagement.

Powerful post with great commentary on the “traits” – thank you!!

I was introduced to the White Supremacy at Work framework at a training where each of the traits was on a card. There were about 30 cards total. As a staff, we each picked out the top three we saw as most active & problematic in our organization. We re-sorted them and picked 5 to prioritize and work to disrupt in the following year. It was an important and challenging exercise. I think of it often.

Thank you for this terrific article, and especially for anchoring it with a very real and illuminating story that described not only the situation–what happened–but its impact in human terms.

[…] Uncovering White Supremacy Culture in Museum Work by nikhil trivedi, Hannah Heller and Joanne Jones Rizzi (click here) […]

[…] [4] https://incluseum.com/2020/03/04/white-supremacy-culture-museum/ […]

[…] white dominant culture in museums, see my previous post here and a really good Incluseum post here). When we use the words ‘leader’ and ‘leadership,’ we are too often only thinking of the […]

[…] & white dominant culture in museums, see my earlier post here and a really good Incluseum post here). So it makes some sense that you are feeling resistance to any suggestion that you uproot these […]